BBC NEWS

- 21 November 2016

- From the section Middle East

Weapons

meant for Western-backed rebels in Syria are ending up in the hands of

so-called Islamic State in neighbouring Iraq - but how are they getting

there?

James Bevan and his small team step carefully into a residential house in Qaraqosh, not far from Mosul in Iraq. A long trail of blood by the entrance and near-ready suicide vests just inside the door confirm what they have been told by a local militia group - this was a position used by fighters from so-called Islamic State (IS).

The team are from the group Conflict Armament Research (CAR). The investigators carry only notebooks and cameras as they hunt for evidence.

Bedding, clothes and remnants of life from the family that once lived there litter the house. But in a backroom, they find what they are after - empty boxes of ammunition.

They shout out details as they take notes and photos. Their aim is to understand how weapons get into the wrong hands.

"To date, the international community has been blind to the fact that weapons are being diverted into conflict affected areas," Mr Bevan explains.

These will be then fed into a database as they trace how the material got from the factory where it was manufactured into the middle of a conflict zone.

Bomb-making 'recipe'

Qaraqosh, a predominantly Christian town, is a scene of near-apocalyptic devastation - buildings smashed to pieces, craters in roads, church steeples toppled over.The streets are eerily quiet. All the residents left when IS came. IS was pushed out only at the end of last month as part of the offensive on Mosul.

By day, a local Christian militia patrols the town but word is that, at night, IS fighters sometimes return.

After that they fled to Irbil and have returned briefly to see what remains.

Pictures around the altar have been torn down and the building ransacked. Inside the church's hall, the CAR team find evidence that the site has also been used as an IS weapons factory.

The parts for rockets are scattered across the floor. Lying next to a bowl of chemicals is a handwritten "recipe" to mix explosives.

IS tried to mass-produce weaponry in areas it controlled and set up home-made mortar factories, but there is also evidence of materials that have come from abroad.

Mass purchases

Around the church pews are bags of industrial chemical - the CAR team have seen these before. It is sold purely on the domestic market in Turkey but large quantities made it into IS hands."When we look at improvised weapons and homemade explosives, we know they buy in massive bulk and they buy primarily on the Turkish market," says Mr Bevan.

"Their procurement networks reach out into southern Turkey and they obviously have a series of very strong relationships with very big distributors."

"Someone has gone up and bought half the stock of a factory," he says.

IS has had no problem arming itself - and the work of CAR suggests that this may partly have been thanks to the weapons sent into the conflict zone by those fighting it.

Turkey conduit

The arms trade is a murky world but Mr Bevan's team has found evidence on the source of IS ammunition.In the early phase of the conflict, most of it was captured on the battlefield from Iraqi and Syrian forces. But from the end of 2015, the team started to see another significant source.

Ammunition boxes were turning up that could be traced back to factories in Eastern Europe.

The team approached manufacturing states to request information to find out to whom the material was sold.

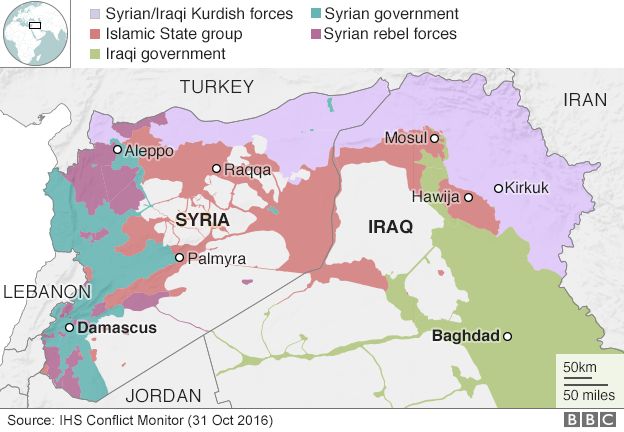

The destination was northern Syria and the opposition groups (which the US and Saudi Arabia supported) fighting President Bashar al-Assad.

The intention was never for the ammunition to find its way to IS but somewhere along the way it was diverted.

This ammunition was found in Tikrit, Ramadi, Falluja and now Mosul - all places where it has been used to fight the US-backed Iraqi forces.

The speed with which IS was getting this material was startling - sometimes only two months from leaving the factory.

"If you supply weapons and ammunition not only to non-state actors but to non-state actors in a very complex interlocked conflict then the risk of diversion is very, very high," says Mr Bevan.

Stemming the flow

Perhaps the closest parallel to the problems of covert weapons supply and diversion is the support given by the US and others to the mujahideen fighting the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in the 1980s.In that case, weapons were sent to certain groups approved by the CIA but were funnelled through Pakistan's intelligence service and sometimes found their way into the hands of other groups fighting the Soviet Union who had more extreme agendas, among them Osama Bin Laden.

Mr Bevan believes establishing the route of weapons is the first stage to preventing diversion.

"We are able to go back to the manufacturer and say these are your weapons and we know that you transferred them legally but your export recipient has transferred them here without authorisation. So you have a problem and now you need to do something about it."

The evidence of the destruction wreaked by weapons lies everywhere in Iraq and Syria. Trying to restrict the flow will not be easy so long as outside states are supporting their own proxy groups.

And in the chaos of this conflict there is no guarantee who will end up getting their hands on weapons and how they will use them.

Read more: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-38048482

No comments:

Post a Comment