CNN

What the world's prison systems can learn from Kenya

August 10 is International Prisoner Justice Day. We take a look in this feature and accompanying video at some of the ways the Kenyan prison service is helping to transform prisoners' lives.

(CNN)When

Peter Ouko was sentenced to death for murder 20 years ago, he was sent

to Kenya's Kamiti maximum security prison, notorious for being one of

the worst jails in the world.

The

prison was modeled on an old-style colonial system, torture was

widespread, and inmates were forced to sleep on the floor amid squalor

and unsanitary, overcrowded conditions.

Ouko

was sometimes locked up in a small cell with 13 other men for 23 and a

half hours a day. Food was not guaranteed, and beatings were frequent.

"When I went to prison in 1998 it was pure torture, and for the first five years, I saw bad things happening," he said.

Ouko

faced an endless wait for his executioner as he resigned himself to his

fate, far away from his two young children and his old life as a

successful interior designer.

He

also thought often of his wife. His dead wife, whom he was accused of

murdering after her body was found near a police station in 1998. Ouko

rushed to the site, only to find himself immediately arrested for her

murder at the scene. He believes he was framed.

"It

was devastating, but I felt that someone wanted to get to me. It wasn't

about getting justice because I believe that if it was about justice,

we could have worked together to get that justice."

He

would spend two years awaiting trial and his children were taken away

from him. Ouko later found out they were told he was dead.

Becoming a lawyer

But

the arrival of one man to the Kenyan political scene in 2003 would

drastically change the fortunes of Kamiti prison-- and Ouko's.

"We had a new vice president who brought the humane touch to the prisons department," Ouko says.

That vice president was Moody Awori or as he was popularly known, Uncle Moody.

"It

was a big deal when Uncle Moody came and decided to change everything.

The first thing, he outlawed torture. He replaced the baton with the

pen, " recalls Ouko.

Most

importantly, Moody started to treat the inmates like human beings,

providing mattresses and bedding for the prison service for the first

time, as well as access to healthcare.

"We

used to be carried in cramped up prison trucks where we could be packed

like sardines. It used to be called Maria. But when Uncle Moody came,

he brought buses where inmates could sit and be taken to court, and we

started calling them Moody Hoppers," he says.

But the most significant change at Kamiti -- and the one that changed Ouko's life -- was the focus on prisoner education.

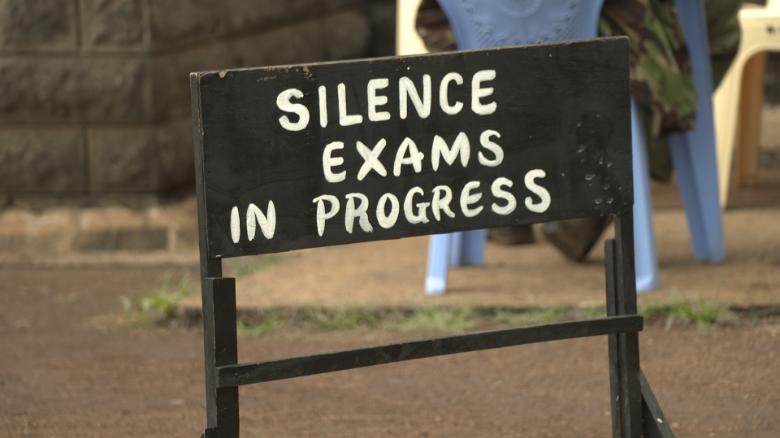

In 2014, Ouko became the first Kenyan inmate to earn a law diploma behind bars.

However,

studying behind bars was not easy. It meant having to balance numerous

court trips, writing appeals pro-bono for his colleagues and advising

them on how to make their presentations in court.

Being

the most qualified "lawyer" among 2,000 inmates was daunting, but

people outside the prison walls were demanding his service too.

He

recalls that a Kenyan who watched his graduation on TV visited Kamiti

prison and requested his help to draft a petition to sue his employers

who had allowed their dogs to bite him.

The

man later came back to say he had been awarded $10,000, signaling to

Ouko that his education was not only useful in helping inmates, but poor

Kenyans too.

The African Prisons Project

Ouko's education was made possible by Awori's reforms and the efforts of the African Prisons Project.

African

Prisons Project (APP), a charity founded in 2007 by UK barrister

Alexander McLean, works to provide education and healthcare in prisons

on the continent.

McLean was

inspired to set up the charity after helping to treat prisoners in

Uganda while volunteering at a hospital in his teens and saw how little

value was placed on some people's lives, especially the poorer patients.

"I realized that there are people whose lives aren't valued by their societies, who live and die like dogs," McLean says.

The

APP trains prisoners and prison staff as lawyers. So far, 3,000 people

have been released from the Ugandan and Kenyan prisons after getting

legal services from those the APP has trained, according to its figures.

By 2020, they have ambitions to release 30,000 people from prison through their trainees.

"Our

students have been involved in several Supreme Court cases, including

one which resulted in the abolition of the mandatory death sentence in

Uganda," he added.

The APP will also create a first-of-its-kind law college in a Kenyan prison, which will open in 2020.

Breaking down barriers

Prisoners

advocating for other prisoners in open court, or advising non-prisoners

on the law, is uncharted territory in Kenya and most places in the

world.

These are the kind of reforms that have got people talking about the Kenyan prison system.

Kamiti now has a well-stocked library, industrial workshops, and the option for other students to study for law degrees.

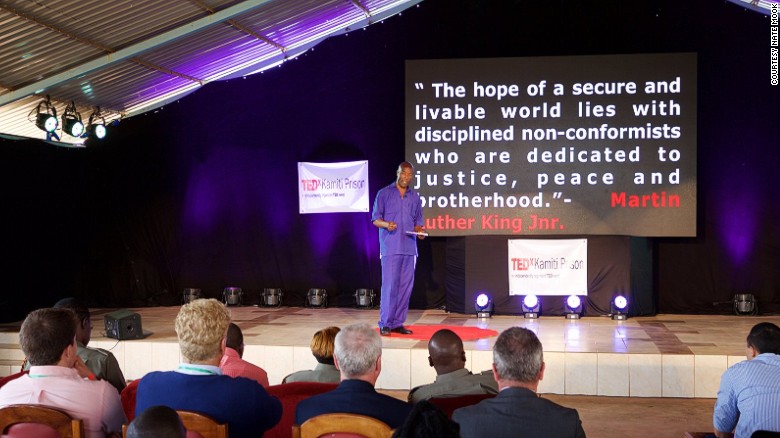

They have organized a TEDx conference at Kamiti prison, and prisoners are learning mindfulness techniques.

Significantly, the barrier between prisoners and prison staff have been broken down.

"We

try to bring everybody on board, the prison officers, the prisoners --

we are a team," said Vincent Gumbi, a warden at Kamiti prison. " We

cannot achieve when we get walls between the prisoners and the prison

officers."

McLean says he has seen

a transformation in the attitude of prison staff. "We work together as a

family of prisoners and prison staff, " he says.

"We

have law classes where prisoners would be teaching the prison staff

law. Some of the staff we work with say 'before I started working with

you, I took joy in beating up prisoners. Now my joy is winning them

their freedom using the legal knowledge that I've acquired.'"

The

UNODC Global Maritime Crime Programme, which offers training and

support in Kenya's maximum security prisons, lauded the "excellent

relationship between officers and prisoners" in Kenya.

A

spokesman for UNODC said it's "significantly important for both

security and management of prisons as well as supporting rehabilitation

of individuals. Also, prisoners have access to family and friends as

well as access to rehabilitation services including vocational training

and education."

'Crime is not cool'

In

2016, Kenya commuted the death sentences of all prisoners to life

sentences and gave prisoners the right to vote for the first time in the

2017 elections.

Ouko was also

officially pardoned by Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and released from

prison after 18 years behind bars in October 2016. His death sentence

had been commuted to life in 2009.

Since his release, he has given a TED talk about his experiences and

now devotes his time to defending the rights of African prisoners

through his prison charity Crime Si Poa, which is Swahili for "crime is

not cool."

"The inmates who had

been released, we use them to engage the community. Go to schools and

speak to them... go out to the communities, we help them build cohesion.

We help them build peace in conflict areas," Ouko says.

US

prisons are already looking to other countries such as Norway for ideas

on prison reform, but Ouko thinks they shouldn't be afraid to look

further afield.

"It's a global

village. It doesn't have to come from the west to Africa. I'd like to

invite the administrators of the prisons in America and the Western

prisons to come to visit Kenyan prisons because there are best practices

to learn," Ouko says.

"You walk

into a maximum Kenyan prison, and you see people busy doing stuff. It

builds hope. It brings down the level of recidivism. It brings down the

level of tension in prisons. You shouldn't lock someone for 23 hours a

day. I was locked up. It didn't help me. It made me resentful and

angry," he adds.

It is a view

echoed by McLean, who says there are models of prisoner rehabilitation

being developed in Kenya's prisons that should be emulated worldwide.

He says "in Kenya, there's a sense that anything is possible in prison."

In contrast, McLean says, the UK had a high number of prisoner suicides in 2016.

"Billions

and billions of dollars are being spent imprisoning people. Our

recidivism rates are high and often prisons are characterized by

hopelessness," McLean says.

"There

are unbelievable lessons countries like the United States could learn

about making prisons humane places where lives are transformed, thereby

making society safer because people leave prison different from how they

went in.

"I look forward to seeing exciting best practices being taken from Africa to the West."

No comments:

Post a Comment