- guardian.co.uk,

- Article history

Jeff Williams, Andy's father. Photograph: Fotovitamina for the Guardian

Andy Williams

On the morning of 5 March 2001, Andy Williams, who had just

turned 15, took his father's long-barrelled .22-calibre revolver and 40

bullets to his high school in Santee, California,

in his backpack. Opening fire in the school toilets and then in the

school quad, he shot dead Bryan Zuckor, 14, and Randy Gordon, 17, and

wounded 13 others, 11 of them students.

On the morning of 5 March 2001, Andy Williams, who had just

turned 15, took his father's long-barrelled .22-calibre revolver and 40

bullets to his high school in Santee, California,

in his backpack. Opening fire in the school toilets and then in the

school quad, he shot dead Bryan Zuckor, 14, and Randy Gordon, 17, and

wounded 13 others, 11 of them students.In the weeks before the shootings, it later transpired, Williams had told as many as a dozen people he was going to "pull a Columbine". After the shootings, Williams told investigators he was "tired of being bullied". A fellow student said others would "walk up to him and sock him in the face for no reason". Williams also claimed to be influenced by the rap-metal band Linkin Park, whose song One Step Closer included the lyrics, "Cause I'm one step closer to the edge, and I'm about to break".

Williams was charged as an adult. After pleading guilty, he was sentenced to 50 years to life, which he is now serving in Ironwood state prison in Blythe, California. Now 25, he will be eligible for parole in 2052, when he is 66.

"I feel horrible about it because I am so ashamed," Williams said later. "I can't write it down. I can't tell it out loud how sorry I am."

Jeff Williams, 52, Andy's father, who now lives in Arizona and works as a technician in a university research facility, is hoping Andy can appeal his sentence, which would see him freed much sooner.

Jeff Williams, Andy's father Andy's mother and I divorced in 1990, when he was about four years old. His brother went to live with his mum in South Carolina and Andy stayed with me. We lived in Brunswick, Maryland. His brother would come up in the summer for a week or two and Andy generally went to his mum's at Christmas for about 10 days or two weeks. Otherwise he didn't have much contact with his mum, which made him unhappy. Maybe she would call on his birthday or send a card. Then, when it got down to Christmas time, it was a call or she'd send a letter with the flight instructions, and that was pretty much it.

As a kid, he liked to be a little bit of a joker, to dress funny or walk funny or try to make silly little jokes. He had lots of friends. He wanted to be a helicopter pilot.

He did regular elementary and junior high school activities. He'd get in trouble every now and then for not paying attention in class or goofing off, but got Bs and Cs, which is fine. He played baseball, basketball, football, soccer.

In 2000, we moved to Twentynine Palms, California. He did real well at the junior high. He was the lead in the Charlie Brown play – he played Linus. We have the videos and you can see what he was like as a kid. Almost exactly a year later, he's in the bathroom shooting people.

After six months in Twentynine Palms, we moved to Santee, near San Diego, so I could work there. He wasn't too happy because it was the second move in six months. We had lived in a nice house in Maryland in the woods and here we were in this cramped, dingy apartment in town. The change was really big for him. And Santana High was a really big high school.

He didn't do well in school. By October and the first teacher's conference, I found out he was skipping school and getting lots of detention, and his grades started to fall. The school agreed they would call me if he was skipping or late, so by Christmas he was doing better and went down to see his mum as usual. I guess when he was down there – I didn't know about this until later – he asked if he could move in with her. She said, wait until after you've finished your first year, instead of doing another move.

When he came back, he did OK for a few weeks with the schoolwork. Then he started cutting classes and the grades were really bad: Cs, Ds, I think even one F. I thought it was a rebellious thing, like I was at that age. He picked some bad friends. I would tell him, "I don't like these guys, but that's your choice to hang out with them." It came out later he was smoking marijuana, drinking beer and smoking cigarettes with them.

I think that an older guy would buy the pot and smokes and beer for Andy and his friends in return for sexual favours. Andy has only just started talking about this. I didn't have any idea about all that or what was going on on campus.

Andy was getting badly bullied in school. He had his skateboard stolen twice. The kids would come up with cigarette lighters and burn him in the neck, throw his books in the toilet, take his bags, hit him, do sucker punches. But when he'd come home he'd just say, "Oh, I fell off my skateboard."

He was skinny – most of his friends were a good 20 or 30 pounds heavier than him. I didn't know it then, but he hated going to school because of the abuse. But the friends outside school were pounding on him almost as bad. He would email friends in Maryland and tell how bad it was, but I had no inkling of what was going on in his head.

The Saturday before the shootings I took him hang-gliding for his birthday present. On the Sunday we went to look at a condo I was thinking of buying. He sat there just calm as all, smiling, picking out the room he wanted.

On the morning of 5 March, Monday, I was at work. All of a sudden the local TV stations came on. My supervisor told me, "You'd better go to the school. There's been a shooting and they're asking for the parents to come and get their kids."

I got into Santee about 10.30am. There were all these police cars and ambulances and helicopters and people in uniform all over the place. I walked around this parking lot for two hours, trying to find Andy or kids I recognised. Every few minutes I would call home to see if he had happened to skip school. I was just wanting to find him. I didn't know anyone was killed then – all I knew was there was a shooting and that kids had been hurt and I was hoping that Andy wasn't one of them.

About 12.30 I turned around and these two girls I recognised were bawling. They went, "Andy did it." I felt all the blood just rushing out of me. I went up to the first law enforcement person I saw. "My name is Jeff Williams. I think my son was the shooter." From then until about four or five o'clock, I was questioned by the San Diego Sheriff's office. I asked the sheriff if I could call Andy's mother, because she was going to be worried because it was all over the news, so I called and let her know it was Andy and that he was OK. She just broke up and cried right there.

I wasn't allowed back to the apartment because they were searching it and the media was parked out there. Then, a bit later, as I was driving, they announced on the radio that there were 13 kids wounded and two kids killed. That was it for me. I was in my little car just bawling my eyes out in agony and distress. I couldn't believe it. I couldn't believe Andy had done this.

Andy took my .22 pistol and the bullets that morning. I didn't know it was my gun. I didn't know I even had any bullets. But apparently I had 50-odd in the gun cabinet. In Twentynine Palms, people were breaking into houses and since I was a single parent and by myself, if I was gone and something happened, I wanted Andy to know where the key to the gun cabinet was.

I first saw Andy three days later. We hugged and he started crying and saying he was sorry. I started crying. I wasn't angry with him. It was just incomprehensible to me that this fun-loving kid could change in such a short amount of time and do something like that.

The people at work were very supportive. People from Maryland, Andy's friends, came out to support him. But the people from Santee, I would get threats and nasty letters. I had to move away. I still get letters. People can't seem to forget.

We never went to trial. Andy was charged as an adult and he received an adult sentence, even though he was only 15. If he had gone to trial, the judge said because of the charges it would have been 450 years to life. So we decided to go ahead and plead guilty, and he ended up with a 50-year to life sentence.

I am sorry. I feel terrible for everybody. This is something that didn't need to happen. I think I did everything I could have other than be maybe a little bit more forceful in my interactions with the school and maybe stop him hanging out with those friends.

My lawyer told me not to try to contact the families. Our family gave a statement on TV apologising to them. We said, "There is no way anyone can ever repay the loss they have suffered." The only interaction I had with them was when I met their attorney. The families of the two boys who were killed were suing me for negligence.

It was probably a few months before Andy's mum was able to visit him. She came to a couple of hearings and now visits once or twice a year because she lives out in South Carolina. We don't talk at all now. She feels I am responsible because I was the one looking after Andy.

Andy's in protective custody in prison, with people like rapists who would be killed if they were in the general prison population. Since he's been there he has received his high school diploma.

I see him about once a month. I've been doing this now for 10 and a half years and I'm glad to see him. We catch up on what's going on on the outside, happy stuff, neutral stuff. But it's always depressing, to see somebody who is going to be in prison for another 40 years; he's now 25 years old. In some states he would have been tried as a juvenile and he would be looking at getting out now. He has an attorney who is working pro bono, trying to get a trial, trying to get this sentence reduced, because Andy was a juvenile, he was being sexually abused and he was being badly bullied.

I've never stopped loving Andy. He's my son. He made a terrible mistake, which he will be paying for for the rest of his life, but that doesn't make me stop loving him.

• Interview: Christopher Goodwin

Larry Robison

Lois Robison, Larry's mother. Photograph: Brandon Thibodeaux for the Guardian

In August 1982, Larry Robison, then 25, apparently hearing

voices, murdered five people, including an 11-year-old boy, near Fort

Worth, Texas.

One of the victims, Rickey Bryant, a friend with whom Robison was

living, was shot twice in the head, stabbed 49 times, decapitated and

sexually mutilated.

Lois Robison, Larry's mother. Photograph: Brandon Thibodeaux for the Guardian

In August 1982, Larry Robison, then 25, apparently hearing

voices, murdered five people, including an 11-year-old boy, near Fort

Worth, Texas.

One of the victims, Rickey Bryant, a friend with whom Robison was

living, was shot twice in the head, stabbed 49 times, decapitated and

sexually mutilated.  The victims were: Rickey Bryant, 31; Georgia Reed, 34; Scott

Reed, 11; Earline Barker, 55; and Bruce Gardner, 33. Although Robison

had been diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic, he was judged sane for

trial and sentenced to death in 1983. After a retrial in 1987 and a

last-minute stay of execution, Robison, then 42, was executed in 2000.

Lois Robison, Larry's mother, now 78, a retired teacher, and her

husband Ken, Larry's stepfather, have since campaigned to get better

treatment for people with severe mental illness and to stop the

execution of mentally ill people.

The victims were: Rickey Bryant, 31; Georgia Reed, 34; Scott

Reed, 11; Earline Barker, 55; and Bruce Gardner, 33. Although Robison

had been diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic, he was judged sane for

trial and sentenced to death in 1983. After a retrial in 1987 and a

last-minute stay of execution, Robison, then 42, was executed in 2000.

Lois Robison, Larry's mother, now 78, a retired teacher, and her

husband Ken, Larry's stepfather, have since campaigned to get better

treatment for people with severe mental illness and to stop the

execution of mentally ill people.Lois Robison, Larry's mother Larry was my oldest son. His father died when he was two. He was a great little boy. I like to say he was every mother's dream. He was smart. He loved to read. He won honours in the Boy Scouts.

He did real well until he became a teenager and started having behavioural problems, like streaking through the gym at school. He had trouble in the class. He played hooky, tried to run away from home. He ran two or three blocks away. We finally got him in the car. He was like a wild animal, afraid. His eyes looked frightened. He was closed down. He didn't want to talk about things. Ken found drugs in his bedroom, amphetamines and stuff. Later, Larry broke into our church and stole food.

We called our youth director at church, and he came and talked to him. We got him into psychiatric treatment, but they didn't do a very good job of diagnosing children at that time. The psychiatrist said we were being too strict, that we should loosen up, let him go out on his own more. Things just deteriorated.

He left home and quit school in senior year, and went to live with some guys in an abandoned house. Every time I drive by that house, I think about that. Larry came home one time and said his roommates were plotting against him, they were trying to kill him, all kinds of strange things. One time he called and said he knew what was wrong with him. He said he had been flying out of his body over the streets, singing the song of his life, and he wanted to know if it had been on TV. He was deteriorating physically. We were wringing our hands; we didn't know what to do. We tried to get him help from the time he was 12 until he was 25.

When he was about 21, he ended up in jail. I talked to his lawyer. He said talk to the DA. I talked to the DA. He told me to talk to the judge. Guess what the judge told me? There wasn't anything he could do.

We took him to see our family doctor. He called in a psychiatrist. They said it was paranoid schizophrenia: the worst case they had seen. So they put him in hospital, but he walked out. They couldn't leave him alone, so asked me to sit with him. He was talking to the TV and getting secret messages from it. They put him on some drugs, but the drugs made him walk like a zombie. He said, "Mum, do you notice how funny I walk? I think it's that medicine they're giving me." All they could do was keep him in for 30 days, then they had to turn him loose [because he wasn't violent or a threat to himself]. They can't do anything to help people like Larry, but they darned sure can commit them to death row when finally something happens.

We woke up one morning to the news that five people had been killed in Fort Worth. I told Ken, "I heard the strangest thing on the radio. They said a Larry Keith Robison had been extradited from Kansas." Ken almost fell down, saying, "Oh, no! Oh, no!" He had heard everything about the killings at work, except the name.

I decided I had to let people know Larry was mentally ill, and to try to get help for him in prison. So I was speaking out on radio and television. One woman, a relative of the victims, she wrote me a real hateful letter saying, "Lois Robison, shut up! When they execute your son, we are going to be there cheering!"

But a lot of people were really kind. When the news broke that Larry had been arrested, it wasn't an hour until our house was full of our friends. The people from church brought food. At school I had people come up and put their arms around me and say they were praying for our family.

Larry's lawyer told me not to try to contact the victims' families, but I asked an official who knew them to tell them that our family was so sorry for what happened and that if there was any way we could have prevented it, we would have.

But I didn't feel responsible because I knew we went through every possible avenue to get help for Larry since he was 12. What happened was a horrible thing, but it didn't affect the way I felt about Larry. Larry in his right mind would never have done such a thing. I think I never loved him as much as I did when I found out this happened.

It was a year before they tried him. I passed out at the trial. I totally collapsed. They put me in the hospital. My poor husband had to tell me they had found Larry guilty and sentenced him to death.

The prosecutors said the most horrible things about me: that she's lying; she never tried to get help for him; she always got him out of trouble and she's here today to get him out of trouble again. I went up to them after it was over and said, "Would you work with us, so mentally ill people can get treatment so this won't happen to other people?" And they just gave me a cursing.

When Larry had his last hearing, to try to stop the execution, he asked to speak to the families in the courtroom. He said, "I didn't want this hearing, but there are people in this room who love me and they don't want me to die. I'm sorry if it's put you through any more pain."

At the execution, the families of the victims were there. I remember the police telling our lawyer to keep me back because there were threats on my life. They did not like it that I was saying that Larry was mentally ill. They said that Larry wasn't mentally ill, that he was just mean. I recognise that's the way some people feel. The victims' families have the right to feel any way they want to feel. They're the ones who have been hurt.

When Ken first heard Larry had killed those people, he'd said, "We've got two choices: we can crawl into a cave and pull a rock in after us, or we can try to do something to make something good come out of this." So we opted to do that. We founded an organisation called Hope – Help Our Prisoners Exist – that fights for prisoners on death row. We've travelled all over the world with Murder Victims' Families for Human Rights – people who fight against the death penalty.

We always stressed prevention, because when somebody has gone mad and killed somebody, you can't undo that. Unfortunately there's still not much help for the mentally ill. Maybe one day things will change. You know the guy who shot that politician, Gabrielle Giffords? I took one look at that guy and I could tell he was mentally ill. On death row, about a third of the people are mentally ill. What they do is treat them until they are better so they can execute them. Isn't that lovely?

I was outside the prison when they executed him, with our family and hundreds of friends and supporters. It was an ordeal, but we had already been through it once when they stayed his execution. We had been grieving for a long time.

I don't think I could have lived through it if we hadn't been doing something about it. That's what saved my sanity, going out with the abolitionists, marching, trying to educate people. I've been told we've made a difference. I hope we have helped, because that's what we set out to do, to try to prevent it from happening again.

• Interview: Christopher Goodwin

Steven Grieveson

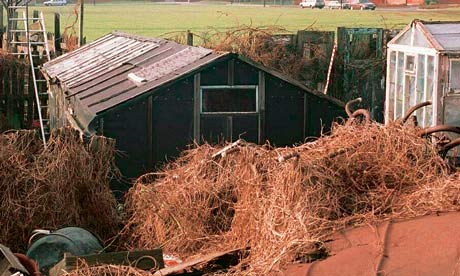

The allotment where the body of one of Steven Grieveson's three

teenage victims was found. Photograph: North News & Pictures

Steven Grieveson, 40, is serving life for the murder of three

teenage boys in Sunderland – Thomas Kelly, 18, and 15-year-olds David

Grieff and David Hanson. He pleaded not guilty, but was convicted in

1996.

The allotment where the body of one of Steven Grieveson's three

teenage victims was found. Photograph: North News & Pictures

Steven Grieveson, 40, is serving life for the murder of three

teenage boys in Sunderland – Thomas Kelly, 18, and 15-year-olds David

Grieff and David Hanson. He pleaded not guilty, but was convicted in

1996.  In 2004, he wrote a letter to the Victim Liaison Service,

admitting the murders. Grieveson strangled and burned his victims. The

prosecution alleged he murdered the boys to stop them revealing he was

gay. He was given three life sentences and ordered to serve a minimum of

35 years. He has also been questioned about another unsolved murder.

In 2004, he wrote a letter to the Victim Liaison Service,

admitting the murders. Grieveson strangled and burned his victims. The

prosecution alleged he murdered the boys to stop them revealing he was

gay. He was given three life sentences and ordered to serve a minimum of

35 years. He has also been questioned about another unsolved murder. Cathy, Steven's mother Steven was a good little boy till he was 11, when he started getting into trouble. He was one of seven children I had with my husband. Steven was a mammy's boy. Still is. He just got into mischief.

It was only me Steven's dad hit. But it wasn't one-sided. I gave back. I wouldn't shut up. It was a violent relationship. More than likely that had an effect on the kids. At 11, Steven got taken to court for pinching a nail. He opened a packet of nails and nicked one, and that was that. Before that he'd been cautioned a few times. By then I was a single mum, and the courts took your kids off you if they got into trouble.

Steven was a really loving boy. When they sent him to the children's home in Carlisle, he was still loving. The care order lasted till he was 18, though he came back at weekends and I'd sometimes go up to see him with social services.

Steven never talked to me about his experience there, but it later emerged there was sexual and physical abuse at the home and it got closed down.

I felt bad when he was sent away, like I might not have brought him up properly. It wasn't just him; my oldest had also gone into care. I wasn't always there for them, because I used to go to the bingo and that. There's no point lying because that's what I did, but I didn't turn him into a killer.

He was still getting into trouble when he came back from Carlisle. He was 18, smoking a lot of dope, taking sleeping tablets and sniffing glue. He was always into cars, nicking them or buying them with stolen money. I knew he was burgling places because the house was getting searched every other week when he lived at home.

I used to scream and shout at him, but it made no difference. The police would come at 7am when everybody could see. At one point there was a stolen car in the backyard. I said, "What's that doing there?" but Steven denied he had taken it.

He was always in and out of prison – 38 convictions since he was 12 for stealing. He never did a long sentence, though, until he went down for murder.

I was convinced he was innocent. The first time I was allowed to see him after they charged him, he said, "Mam, I didn't do it." At the beginning I believed him, because even the solicitor said, "Your son's not a murderer." Steven has never admitted to me he killed the three boys, though he has to others. I don't know if it's because we're so close and that makes it harder.

When he got charged on 5 November 1995, he said he had been abused, and maybe he was abused when he was away from home. I don't know if that had anything to do with it. I know he's homosexual, too, and he's never talked to me about that. Steven was a good-looking lad and still is. He did have relationships with girls, but he never enjoyed them. I think he found that very difficult to cope with, especially in a place like Sunderland.

When I read the details of the murders, I felt sick. Awful. He'd already killed them, so why burn them? I still have nightmares about it. I can see it happening. When he was found guilty I was put on Valium. I'm still on sleeping tablets now.

It was straight after he got charged that the attacks started. I was living in Roker Avenue when everything happened, and the day Steven got charged somebody came and put all my windows out. I went out and ran after them. I was scared. That was the Sunday and the following Friday a 14-pound hammer came through my window.

I went to court in Leeds for Steven's trial. I went to the toilet and one of the relations followed me and said, "You're going to get a good hiding" and I said, "If you think you can do it, do it, but I'll fight back." I didn't go back to court after that. My sister told me he had been found guilty. I did think he'd walk away, but there was always a big doubt in the back of my mind – what if he's not innocent?

I want to know why he did it, but I can't bring myself to ask him. I always hoped he'd tell me. I'm still waiting. I've always thought there must be something wrong with him; that he is mentally ill.

People didn't stand by me. I used to go drinking in the clubs and pubs with people I thought were my friends, but when everything happened I realised I didn't have any friends. I feel that even Steven's friends were trying to distance themselves from him.

The Sunderland Echo didn't make it any easier by doorstepping me. Then again, I didn't make it any easier for myself by going on television – I said I didn't think my son was a killer. That probably made it worse. They treated me like I'd killed the boys. Social services helped me. They moved out my two youngest daughters, who were 14 and 15, so it was just me at home. Then they said I'd better move away and adopt a new identity.

Since then I've moved about 10 times. When people find out whose mother you are, they can be very vindictive. Sometimes I've been recognised, and within the next breath it's all round the streets. When I moved south I hoped I'd be able to start a new life, but I couldn't. Somebody sent an anonymous letter, with the photo of another murdered boy Steven has been questioned about.

In 1998 I went to jail after getting caught taking marijuana into prison for Steven. Why did I take the drugs in? I suppose it was a mix of love and guilt; again, the guilt that I didn't bring him up right and the guilt I feel when he says, "I can't go on." I thought the drugs would help Steven sleep. I've felt like saying, "Well, you made your bed, now lie in it", but I never have.

I did six months in jail and was given a hard time. When I went into Low Newton prison, somebody recognised me and they were shouting, "Sunderland strangler, Roker Choker, your son's a murderer."

I've just moved again to another city. I still see my kids sometimes, but I don't make friends. It's a lonely life. There is not a day I don't think about Steven and what he did. I still worry that I was a bad parent. I'm not sure what there is to live for. I have been suicidal in the past.

I know Steven will not come out, certainly not when I'm alive. And I'd be terrified if he did – for what he might do. But I still love him. I could never turn against him because he's my son. And he's still a mammy's boy.

• Interview: Simon Hattenstone